Who gets to have a baby, who gets sterilized, and who decides?

An American History of Eugenics: from forced sterilizations to the 2025 Natal Conference.

Wanna make a baby at the Natal Conference?

That could cost you $10,000.

In a recent Fox News interview, Elon Musk said that the declining birthright is what’s keeping him up at night. Turns out, he’s not the only one. If you thought having kids was expensive, imagine going to a far-right matchmaking conference where you could meet the extremist influencer of your dreams (or your nightmares). Well, now you don’t need to imagine. For $500 to $10,000, you can—but only if you fit the bill (for certain views) and can pay the bill.

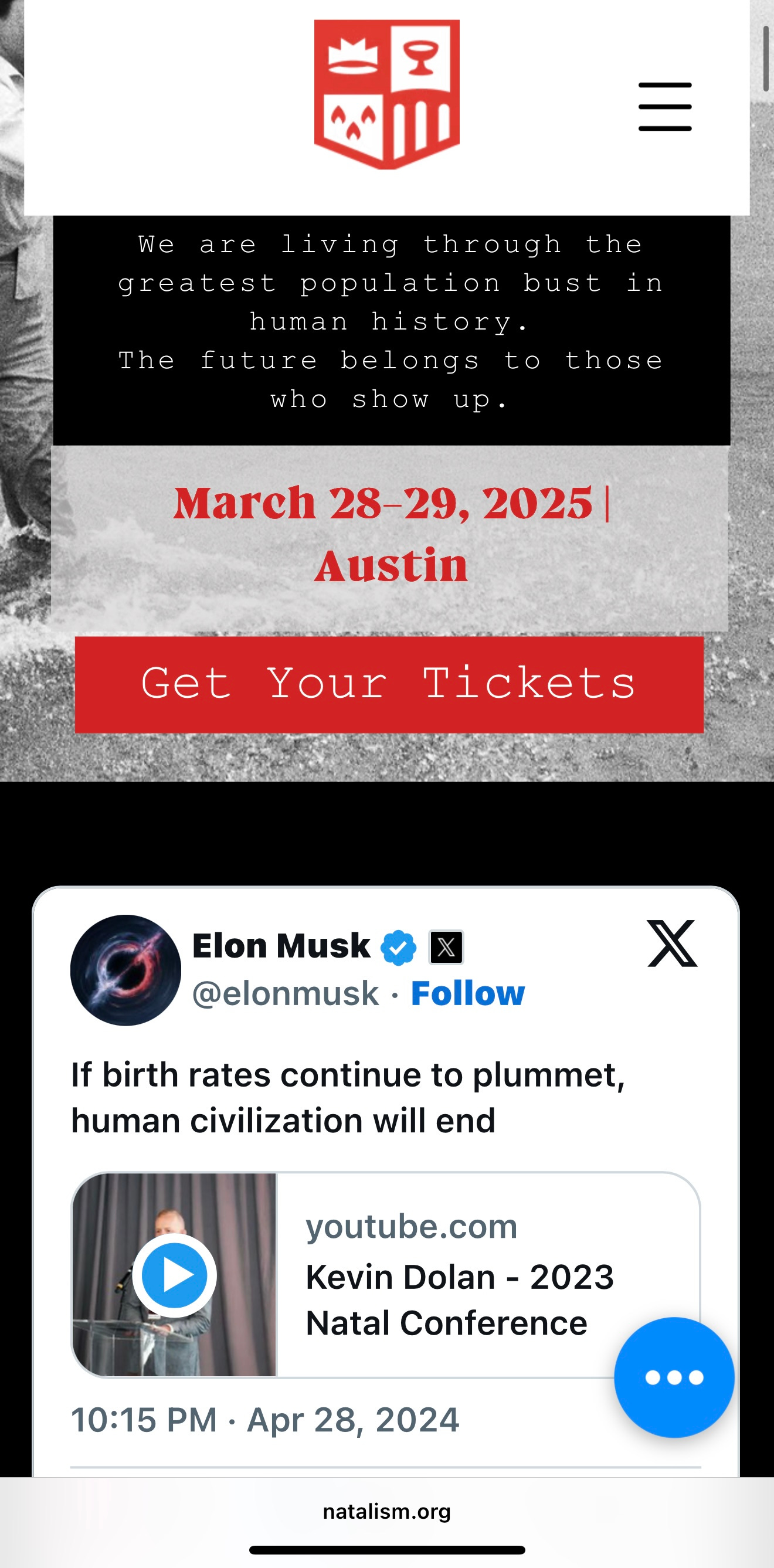

What you need to know: According to WIRED, Far-Right Influencers hosted “a $10K-per-Person Matchmaking Weekend to Repopulate the Earth.” The dates for the second annual Natal Conference were set for March 28th-29th in Texas earlier this year.

The Natal Conference was billed as a celebration of family values and pro-natalism—but the speaker lineup reads more like a roll call for the intellectual rebrand of eugenics.

On the official conference website it reads, “We are gathering the brightest minds in the world in search of new solutions.”

However, when you go through the list of speakers, the terms “best and brightest” seem to be less of an accurate description and more of rebranding of what the Guardian describes as “race-science promoters and eugenicists.”

In many ways, the speaker lineup is your nightmare blunt rotation—unless you identify as a Nazi, in which case the theories of many of the conference speakers were the foundation for your political party.

A screenshot of the Natal Conference website.

Who’s who at the natal conference?

Jonathon Anomaly—whose beliefs are anything but an anomaly at the Natal Conference— is a former academic who now moonlights as a spokesman for what he calls “liberal eugenics” — which is like calling arsenic organic. He worked with “Heliospect Genomics,” a startup offering embryo screening for various traits. On a podcast with far-right influencer Alex Kaschuta, Anomaly described how embryo selection can “boost IQ at least a bit,” with the promise of more enhancements “in the future.” Because what could go wrong when billionaires start designing their children like iPhones?

Then there’s Diana Fleischman, an evolutionary psychologist and “Aporia” contributor. “Aporia” is basically BuzzFeed for race science — it publishes pieces like “You’re Probably a Eugenicist,” which, in this context, feels less like a warning and more like a flirtation. On her Substack, Fleischman amplified a racist Aporia article that used Holocaust victims as a rhetorical cudgel to argue that people of color were innately less intelligent. “Aporia,” by the way, is run by Emil Kirkegaard — a man who’s made a career out of putting a pseudo-academic bowtie on white supremacy.

Speaking of white supremacists, Jordan Lasker is also reported to have been a speaker under an alias. If you don’t recognize his name, it might be because he’s better know by the pseudonym that The Guardian traced him to: “Cremieux”—the pseudonymous race science evangelist who somehow convinced Elon Musk to become his biggest fanboy.

Musk has reposted and replied to Cremieux’s musings about declining birth rates and crime in Portland like he’s quoting scripture. Lasker’s Substack (under the Cremieux handle) has published pieces defending the long-debunked theory that national IQs vary by up to 40 points along racial and geographic lines, which is based on Richard Lynn’s work.

Richard Lynn was a man so steeped in scientific racism that even Psychological Science and The Royal Society walked it back. He was proudly affiliated with the Pioneer Fund, white nationalist conferences, and Mankind Quarterly. Lasker not only platforms Lynn’s work, but he’s also tried to resurrect it under his own name, co-authoring a paper with Bryan Pesta (fired) and Emil Kirkegaard (see above).

Jason Wilson reported that “when the Guardian reached out on that Lasker-linked email to ask about the registration and other evidence pointing to his operation of the Cremieux, Lasker replied with a message containing a promotional code for discounted subscriptions to the Cremieux Substack.” (The Guardian)

Because when in doubt, monetize the fascism. (Sarcasm.)

Also in the lineup: Charles Cornish-Dale — a.k.a. Raw Egg Nationalist— who has spent his far right-influencer career pushing neofascist aesthetics, conspiracies, the Great Replacement theory, and pictures of steak, all while allegedly living with his mom in South Dorset.

Alongside him is Jonathan Keeperman, better known as “L0m3z,”who runs the far-right publishing house Passage Press — essentially an MFA program for incels with Substacks.

And of course, no dystopian circus would be complete without Malcolm and Simone Collins — the “hipster eugenicists” who pitched a startup dictatorship on the Isle of Man where voting rights are earned by producing economically valuable children. Yes, really. They called it a city-state; we call it eugenics.

While the far-right Natal Conference might have been promoted as part of a “search of new solutions,” (their words, not mine) many of the theories underpinning its so-called “solutions” are not new, nor are they effective. And if the word “solution” in this context reminds you of Hitler’s “Final Solution,” there’s a reason for that too.

From 1907 through the 1970s, over 60,000 Americans were forcibly sterilized under state eugenics laws. California led the charge, performing more than 20,000 sterilizations in state hospitals—many without consent, and often on people as young as 12. These laws were so influential that Nazi Germany modeled its own sterilization program on California’s (Buck v Bell, Embryo Project Encyclopedia, Arizona Stare University).

So, is “pronatalist” the new word for “eugenicist?”

The blatant undertones of eugenics at the Natal Conference are dangerous, especially because there are other examples of eugenicist language used throughout the Trump administration and its affiliates like Elon Musk.

The resurgence of eugenics rhetoric in right-wing spaces isn’t just academic—it’s weaponized, coded, and deeply embedded in the language used to dehumanize people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. As The Guardian reported in a March 2025 feature, the increasing normalization of the R-word is no linguistic accident. Its use is historically tied to the eugenics-era belief that disabled children were “defective” and ought to be eliminated “for the good of society.” Topher Endress, a reverend and disability theologian, noted that this rhetoric echoes the ideological foundation of eugenics: the notion that society should be engineered by eliminating those deemed unfit to exist within it (Kirkland, The Guardian, 2025).

According to Justin Kirkland at The Guardian, the R-word has entered a new era of prominence in right-wing digital spaces, where slurs are wielded with what he describes as “gleeful relish” to demean ideological enemies (Kirkland, The Guardian, March 2025). Elon Musk alone has used the slur at least 16 times on X in the past year—often to insult public figures who cross him politically. Kirkland points to Musk’s fixation on intellectual “fitness” and his calls to eliminate “unnecessary” social spending—like Medicaid—as part of a broader eugenicist drift.

That drift isn’t limited to Musk. Trump, too, has embraced this rhetoric, reportedly using the R-word to insult both Biden and Kamala Harris, and more recently suggesting that a deadly FAA crash was linked to the hiring of people with psychiatric or intellectual disabilities (Kirkland, The Guardian, March 2025). The throughline here is chilling: according to Kirkland, powerful figures are openly resurrecting the language—and logic—of eugenics, casting disabled people not only as punchlines but as liabilities to national safety (The Guardian).

This derogatory language also evokes dark days in both U.S. and German history. In the early 20th century, U.S. states like Indiana and California passed laws permitting the forced sterilization of people labeled “undesirables,” including those with intellectual disabilities—a practice that would go on to inspire Nazi Germany’s “euthanasia” programs, which killed over 250,000 disabled people in the 1930s and ’40s. In that era, American eugenicists became both ideological allies and cautionary tales: what began as “scientific progressivism” metastasized into genocidal policy (National Library of Medicine, 2024). The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed just 35 years ago. The distance between then and now is shorter than many would like to admit—and the return of this language is a reminder of just how fragile that progress remains.

What does this echo from American history?

Beginning in the early 1900s, many U.S. states implemented eugenics laws aimed at preventing certain people from reproducing. Indiana passed the first forced sterilization law in 1907, and eventually 32 states enacted similar laws. (“Belly of the Beast: California's dark history of forced sterilizations,” The Guardian, Shilpa Jindia)

These laws targeted those deemed “unfit”—often people with intellectual disabilities, mental illness, epilepsy, or those living in poverty. The U.S. Supreme Court cemented the legality of such practices in Buck v. Bell (1927), which set the precedent that states “may sterilize inmates of public institutions” without violating the Constitution (Buck v. Bell, 1927, as cited in Embryo Project Encyclopedia).

In that case, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes declared “three generations of imbeciles are enough,” upholding Virginia’s sterilization of Carrie Buck. The ruling bolstered America’s eugenics movement, providing legal authority for the forced sterilization of over 60,000 people across the country up until the 1970s. Notably, Buck v. Bell has never been explicitly overturned, remaining a chilling precedent even though eugenic sterilization programs have since been discredited (Buck v. Bell, 1927, as cited in Embryo Project Encyclopedia).

The Guardian’s Shiloh Jindia reported:

“From 1909 to 1979, under the state eugenics laws, California forcibly sterilized about 20,000 people in state institutions who were deemed ‘unfit to produce.’ The program disproportionately targeted the Latino community, women, people with disabilities and impairments – even those who had children out of wedlock. The mean age of victims was 17, and they included children as young as 12.

Among the arguments for the state’s policy were the same cost-benefit rationalization echoed in the rhetoric around sterilizations in state prisons nearly a century later.”

Hitler’s regime looked to California’s law as a model when crafting the 1933 German sterilization statute. California formally kept its eugenics law on the books until 1979, and it was among the last states to halt the practice. Today we recognize these policies as grave violations of human rights, and in recent years California has even moved toward compensating surviving victims.

By the 1970s, growing public outcry and lawsuits finally began dismantling eugenics programs. Many states repealed their sterilization laws (for example, Virginia did so in 1974, and Oregon performed its last sterilization in 1981). The horrors of Nazi eugenics also cast an ugly shadow that helped turn public opinion. Although the formal eugenics era ended, its legacy—the idea that the state can decide who is “fit” to have children—has persisted in various guises.

Throughout the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of Americans with disabilities or mental illness were segregated from society in large state-run institutions. The treatment in these facilities was often inhumane. Many were overcrowded, under-resourced “warehouse” asylums that subjected residents to neglect and abuse. A notorious example is Willowbrook State School in New York, an institution for children with developmental disabilities (Rivera, 1972).

In 1972, reporter Geraldo Rivera conducted an exposé of Willowbrook, revealing “deplorable conditions, including overcrowding, inadequate sanitary facilities, and physical and sexual abuse.” Scenes from Willowbrook showed children naked and unattended, living in filth—a place described as a “snake pit” by witnesses . The public was horrified. Rivera’s televised report sparked a national outcry that led to Willowbrook’s eventual closure in 1987 and helped prompt federal civil rights legislation to protect people with disabilities. (Rivera, 1972; Wikipedia)

Willowbrook was not an isolated case; it exemplified a widespread pattern. For decades, society’s solution for those with intellectual or psychiatric disabilities was to lock them away, often for life. Conditions in many state institutions (Pennhurst in Pennsylvania, Letchworth Village in New York, the Fernald School in Massachusetts, to name a few) were similarly appalling. Basic human freedoms were denied—residents had little control over their lives or bodies. Many were subject to medical procedures without consent, including forced sterilizations under the eugenics laws described earlier. It wasn’t until the latter half of the 20th century that this began to change. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy – influenced by his own sister’s tragic lobotomy – urged reforms to end the “reliance on the cold mercy of custodial isolation” for the mentally ill (The Atlantic, “RFK Jr.’s 18th-Century Idea About Mental Health,”Shayla Love).

The 1970s saw landmark lawsuits and legislation that established rights to education and community-based care for people with disabilities (for example, the Willowbrook class-action suit and the federal Developmental Disabilities Assistance bill). These efforts gradually shifted care from institutions to community settings in a process known as deinstitutionalization. But the abuses of the past cast a long shadow. They demonstrate how easily a society can strip a vulnerable group of its freedom and dignity in the name of “care” or “order.” The echoes of that era linger in modern proposals, like RFK Jr.’s potential “Wellness Farms,” that might, even unintentionally, revive coercive approaches.

Elon Musk himself, though not an official participant in modern eugenicist circles, has helped bring some of eugenicist talking points into the mainstream. Musk has been very vocal about the danger of “population collapse.” He frequently warns that if people don’t start having more babies, civilization will crumble. The Natal conference organizers even quote Musk on their website: “If birth rates continue to plummet, human civilization will end.” Musk posted this on his X/Twitter account in late 2023, and it’s prominently featured as inspiration for the pro-natalist crowd (Jason Wilson, The Guardian).

Musk’s concern with fertility might be rooted in genuine demographic data (many countries do have falling birthrates), but his focus and language resonate with classic eugenics in one key way: it’s not just about more babies, but about who is having them. By engaging online with the likes of Lasker/Cremieux—and by lamenting “collapse”—Musk flirts with the idea that certain populations need to reproduce more to stave off a doomed society. He has at times hinted at IQ and heredity as well, noting that he himself has many children (at least 13 with three different mothers) and suggesting that intelligent people should have more kids.

Elon Musk’s casual alignment with eugenicist thinking isn’t just theoretical—it has policy implications. As journalist Justin Kirkland argues in an article for The Guardian, Musk’s public rhetoric and online behavior signal a deeper ideological project: one rooted in the historical dehumanization of people with intellectual disabilities (Kirkland, The Guardian, March 2025).

Musk has echoed old eugenics tropes, promoted accounts that push race-IQ theories, and publicly fixated on birthrates and “genetic quality.” And now, with oligarch-level influence and Trump’s blessing, he’s turning that ideology into budget policy. According to Kirkland, Musk’s efforts to slash so-called “unnecessary” government spending include targeting Medicaid—a system that exists to ensure people with disabilities can access healthcare. The implication is chilling: if you believe certain lives are less valuable, then gutting the programs that keep those people alive starts to look, in your mind, like economic efficiency. That’s not fiscal conservatism. That’s eugenics with a spreadsheet.

How’s this for dystopian nonfiction: Ai might come for your job and Elon might “come” for the population. But you won’t need a partner to go down on you if the stock market does. And even if you’re unemployed, you could be sent to one of RFK Jr.’s Wellness Farms!

Speaking of pseudo-wellness…

Are RFK Jr.’s Wellness Farms a rebrand for institutionalization?

What RFK Jr. is proposing with his so-called “wellness farms” is not new. It could be institutionalization with a fresh coat of organic paint.

According to The Center for Racial and Disability Justice (CRDJ), RFK Jr.’s proposals mirror the long and violent history of state-run institutions that warehoused people falsely deemed “unfit” for society—primarily disabled people, poor people, BIPOC individuals, LGBTQ+ communities, and non-conforming women.

What you need to know: From the 19th century through the late 20th, institutions across the U.S. enforced eugenic policies under the guise of care: forced sterilizations, electroshock therapy, chemical castration, conversion therapy, lobotomies, and unpaid labor were routine (CRDJ).

One such institution, the U.S. Narcotic Farm in Lexington, Kentucky, marketed itself as an innovative rehab center. In reality, it was a federally funded site of incarceration.

Opened in 1935, the Narcotic Farm was a combined prison-hospital for people with drug addiction. It was a sprawling facility that could hold 1,000 to 1,500 inmates (termed “patients”), and it was jointly operated by the U.S. Public Health Service and the Bureau of Prisons. The Narcotic Farm had a dual mission: incapacitation and experimentation (Time Magazine). Officially, its goals were to “incarcerate, rehabilitate, and study” individuals addicted to narcotics. In practice, this meant that many inmates—who were often there involuntarily via court order— were put to work on the farm and subjected to medical experiments aimed at understanding addiction (Time Magazine).

Life at the Narcotic Farm blended pastoral therapy with coercion. Inmates worked fields, milked cows, and grew crops on a campus of “rolling green fields, silos, dairy barns”—a setting meant to be idyllic and wholesome (Time Magazine). They were encouraged to pursue hobbies like music; indeed, the facility had music studios and a 1,300-seat theater, and many jazz legends (e.g. Chet Baker, Sonny Rollins) passed through Lexington in the 1940s–50s. But behind this rehabilitative veneer, the Narcotic Farm’s patients were also research subjects (a politically correct term for human lab rats). Government doctors took advantage of the captive population to run experiments—famously, the first large-scale trials of methadone as a treatment for heroin addiction were conducted on inmates there in the late 1940s. Researchers saw the facility as an “ideal setting” to test treatments on people who couldn’t leave (Time magazine).

According to Jan Hoffman for The New York Times, “The program had high relapse rates and was tainted by drug experiments on human subjects.”

By the 1960s, critics viewed the Narcotic Farm as ineffective, and it eventually closed in 1976. While the addiction studies at Lexington paved the way for modern treatments like methadone maintenance, which proved more successful in the long run than the farm itself, The Narcotic Farm stands as a reminder that even “rehabilitation” programs can become tools of incarceration and involuntary experimentation (Time Magazine).

The CRDJ reports more on the dehumanizing mass experimentation that occurred at the Narcotic Farm, where mostly Black and poor patients were subjected to nonconsensual drug testing. Similar patterns were found across asylums, sanatoriums, and “feeble-minded” schools that served less as therapeutic spaces and more as sites of social control and economic exploitation (CRDJ). Its history is directly relevant today as we examine proposals that echo the Narcotic Farm model (Time Magazine).

RFK Jr.’s proposed farm-based institutions continue this legacy. Branded as voluntary alternatives to incarceration, the CRDJ warns that these facilities are likely to be coercive in practice—especially when court-mandated or tied to access to public services. The vision includes psychiatric evaluation, medical oversight, and labor on a farm under the banner of “wellness.” But history makes clear that any system set up to isolate and institutionalize vulnerable people—especially under state control—becomes ripe for abuse.

Perhaps most disturbing is that these policies are being championed by a member of the Kennedy family. President John F. Kennedy made deinstitutionalization a cornerstone of his administration, spurred in part by the horrific treatment of his sister Rosemary, who was lobotomized at 23 and institutionalized for life without her consent. RFK Jr.’s proposals aren’t just historically illiterate—they actively reverse the hard-won progress of the disability rights movement. As CRDJ writes, “This is not wellness. This is a return to eugenics.”

Additional Historical Examples of Systemic Reproductive or Freedom Control

Understanding this history is crucial. It serves as a cautionary tale as we confront new incarnations of old ideas. The tone of these facts is sobering and direct because the stakes—human rights and human dignity—remain as serious now as they ever were.

Mass Sterilization of Women of Color (1970s): In the early 1970s, investigative lawsuits uncovered that tens of thousands of poor women—disproportionately Black and Latina—were being sterilized under U.S. government programs, often without informed consent. In the landmark Relf v. Weinberger case of 1973, two Black sisters (ages 12 and 14 in Alabama) had been unknowingly sterilized; the lawsuit revealed an estimated 100,000 to 150,000 Americans were being sterilized per year under federally funded initiatives at the time (Relf v. Weinberger, Southern Poverty Law Center).

Some women were coerced with threats that their welfare benefits would be cut if they didn’t “agree” to sterilization. The Relf case led to new federal regulations in 1974 prohibiting forced sterilization and requiring informed consent, finally slowing this widespread abuse (Relf v. Weinberger, Southern Poverty Law Center).

Similarly, a government report in 1976 found that in just four IHS (Indian Health Service) regions, over 3,400 Native American women had been sterilized without proper authorization in the early 1970s (“1976: Government Admits Unauthorized Sterilization,” National Library of Medicine).

Historian estimates indicate that perhaps 25% of all Native American women of childbearing age were sterilized between 1970 and 1976, often through pressure or without full understanding (“A 1970 Law Led to the Mass Sterilization,” Time Magazine). These shocking statistics underscore how recently and extensively reproductive freedoms were trampled, targeting minorities under the guise of “family planning.”

Puerto Rico’s Sterilization Campaign: U.S. colonial policy in Puerto Rico led to one of the highest sterilization rates in the world. Starting in the 1930s and intensifying post-World War II, doctors (with U.S. and local government backing) aggressively promoted sterilization as birth control on the island (“The Long History of Forced Sterilization of Latinas,” UnidosUS).

It is estimated that by 1956, about one out of every three Puerto Rican women of childbearing age had been sterilized—many without fully understanding the permanence of the procedure. Often women were misled to believe tubal ligation was easily reversible, or they were pressured immediately after giving birth. This program, sometimes called “La Operación,” was driven by overpopulation fears and economic concerns. It amounted to a mass reproductive control experiment on Latina women. The practice only slowed after activists like the Young Lords in the 1970s brought attention to the issue (“The Long History of Forced Sterilization of Latinas,” UnidosUS).

Madrigal v. Quilligan (1978): This civil rights case exposed the coercive sterilization of Latina women in Los Angeles. Ten Mexican-American women sued the Los Angeles County+USC Medical Center for tying their tubes without proper consent (the women were pressured, often in English-only forms, while in active labor or vulnerable post-delivery). The case, known as the “Madrigal Ten,” documented how Spanish-speaking women were repeatedly asked to sign sterilization consent forms they couldn’t read, at a moment when they were in pain and highly suggestible (“The Long History of Forced Sterilization of Latinas,” UnidosUS).

One 23-year-old plaintiff awoke from what she thought was an emergency C-section to find she’d been sterilized. Although the judge ultimately ruled against the women— astonishingly attributing the issue to miscommunication and even suggesting that having fewer children might be beneficial—the publicity from the trial led to reforms. California changed its consent procedures after 1978, introducing waiting periods and multilingual forms to prevent such abuse (“The Long History of Forced Sterilization of Latinas,” UnidosUS).

Madrigal v. Quilligan stands as a legal example of marginalized women fighting back against systemic control of their fertility; even if they didn’t win the case, they changed the system. It also showed the racist mindsets of some officials at the time, one of whom argued in court that these women’s “culture” made them value large families, discriminatorily implying that sterilization only hurt their feelings, not their rights—a stark illustration of institutional bias. (“The Long History of Forced Sterilization of Latinas,” UnidosUS)

North Carolina’s Eugenics Board: North Carolina had one of the most active eugenics programs, notable because it continued well into the 1960s and targeted many poor Black women. From 1929 to 1974, the state sterilized an estimated 7,600 people deemed “feeble-minded” or otherwise undesirable (“Belly of the Beast: California’s Dark History of Forced Sterilizations,” The Guardian).

Unlike most states, North Carolina’s program actually ramped up after World War II (when eugenics elsewhere was discredited), and by the 1960s the majority of NC’s sterilization victims were Black and female. Case files show teenagers sterilized for reasons like “promiscuity” or being a rape victim. Decades later, North Carolina became one of the first states to reckon with this history: it formally apologized in 2002 and in 2013 approved a compensation program for surviving victims. The NC program provides further evidence of how long and deeply the U.S. engaged in reproductive control policies (“Belly of the Beast: California’s Dark History of Forced Sterilizations,” The Guardian).

“Ugly Laws” and City Ordinances (late 19th–early 20th century): Another form of controlling who could live freely were the so-called “Ugly Laws”—local ordinances (in cities like Chicago, San Francisco, and others) that made it illegal for persons who were diseased, maimed, or disabled to appear in public, so as not to offend “public sensibilities.” For instance, Chicago’s 1881 ordinance forbade people who were “unsightly or disgusting” in appearance from exposing themselves to public view (Susan Schweik).

These laws (enforced into the early 1900s) essentially criminalized physical disability and poverty in public spaces. While not about reproduction, they are part of the same mentality: systematically restricting the freedom of those falsely deemed “unfit” or “undesirable” because of prejudice and bias. They set a precedent that the government could decide who belongs in society. By World War I, most ugly laws faded and were eventually repealed (the last known one in Chicago in 1974), as disability rights and public conscience evolved (Susan Schweik). But the very existence of these laws shows a historical willingness to strip basic freedoms from certain people—mindset shared by eugenicists of that era and a mindset being resurrected by eugenicists of this era.

Sources

Arce, Julissa. “The Long History of Forced Sterilization of Latinas.” UnidosUS, 16 Dec. 2021.Cohen, Adam. Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck

“Far-Right Influencers Are Hosting a $10K-per-Person Matchmaking Weekend to Repopulate the Earth.” WIRED, https://www.wired.com/story/natal-conference-matchmaking/.

Glenn, Melody. “History Exposes a Crucial Flaw in RFK Jr.’s Vision for Treating Drug Addiction.” Time Magazine. January 30th, 2025.

Hoffman, Jan. Kennedy’s Plan for the Drug Crisis: A Network of ‘Healing Farms’. The New York Times. Jan 18, 2025.

Jindia, Shilpa. “Belly of the Beast: California’s Dark History of Forced Sterilizations.” The Guardian, 30 June 2020.

Kennedy’s Plan For The Drug Crisis: A Network of ‘Healing Farms.’ The New York Times, 18 Jan. 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/18/health/rfk-addiction-farms.html

Kirkland, Justin. ‘The basis of eugenics’: Elon Musk and the menacing return of the R-word. The Guardian, 3 Mar. 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/mar/03/r-word-right-wing-rise.

Love, Shayla. “RFK Jr.’s 18th-Century Idea About Mental Health.” The Atlantic, April 4th, 2025.

“Natal Conference to Host Race-Science Promoters.” Texas Ed Equity Blog, 3 Mar. 2025, https://texasedequity.blogspot.com/2025/03/us-natalist-conference-to-host-race.html.

“Natalism.org.” Natalism, https://www.natalism.org.

“Native Voices Timeline: 1976—Government Admits Unauthorized Sterilization of Indian Women.” U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/543.html. Accessed 15 Apr. 2025.

Raup, Christina and Nathalie Antonios, “Buck v. Bell (1927).” Embryo Project Encyclopedia, Arizona State University, https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/buck-v-bell-1927. Accessed 15 Apr. 2025.

“Relf v. Weinberger.” Southern Poverty Law Center, https://www.splcenter.org/resources/civil-rights-case-docket/relf-v-weinberger. Accessed 15 Apr. 2025.

Rivera, Geraldo. Willowbrook: The Last Great Disgrace. WABC-TV, 1972. Archived from the original on 2 Mar. 2014. Accessed 26 Feb. 2014.

“The Long Shadow of Institutionalization: How History Warns Against Trump and RFK Jr.’s Vision.” Medium, Center for Racial and Disability Justice (CRDJ), https://nlawcrdj.medium.com/the-long-shadow-of-institutionalization-how-history-warns-against-trump-and-rfk-jr-s-4fb495ffaf3d.

“The Supreme Court Rulings That Led to 70,000 Forced Sterilizations.” NPR, 7 Mar. 2016, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/03/07/469478098/the-supreme-court-ruling-that-led-to-70-000-forced-sterilizations.

Theobald, Brianna. “A 1970 Law Led to the Mass Sterilization of Native American Women. That History Still Matters.” Time, 27 Nov. 2019, https://time.com/5737080/native-american-sterilization-history/.

“They want America to have more babies. Is this their moment?” NPR, 7 Apr. 2025, https://www.npr.org/2025/04/07/1243303434/pronatalism-natalcon-musk-vance-fertility-birth-rate.

Schweik, Susan. The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public. Berkeley Books.

Stern, Alexandra Minna, et al. “California’s Sterilization Survivors: An Estimate and Call for Redress.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 107, no. 5, May 2017, pp. 727–728, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5308144/.

“Willowbrook State School.” Wikipedia, Accessed 15 Apr. 2025.

Wilson, Jason. “US natalist conference to host race-science promoters and eugenicists.” The Guardian, 3 Mar. 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/mar/03/natal-conference-austin-texas-eugenics.

Things changing and the future is uncertain

Just mind blowing in the worst way…